Arshak Makichyan is the organizer of the Russian climate movement Fridays for Future and has spoken at the UN together with Greta Thunberg. After the start of the war with Ukraine, he publicly announced his anti-war stance and, fearing arrest, left Russia. At the end of October, the Shatursky City Court of the Moscow Region stripped Arshak and his family of their Russian citizenship, which had been their only citizenship.

In 1995, my family left Armenia and moved to Russia because of the economic crisis caused by the war in the Nagorno-Karabakh region: it was hard to feed three children.

I have been an activist for almost four years now. Every Friday I would take part in climate strikes, while additionally organizing the climate movement. As a result, I have been arrested for six days, had a provocateur sent to me who threatened to stab me. And of course, I attracted the attention of the Anti-Extremism Center.

I was not jailed for ten years because I received a lot of international support, I attended international climate talks abroad. After all, it would have made for a pretty bad picture if one of the few Russian climate activists was to be jailed.

The actual reasons for stripping me of my citizenship were my activism in addition to my anti-war stance. I had already received threats of this happening back in 2021, during my nomination to the State Duma. «Yabloko» promised to nominate me and I started the campaign two months before [the registration of candidates]. The campaign was successful enough as a lot of volunteers enrolled to take part and my TikTok videos gathered 150,000 views as well as a lot of likes.

As a result of the threats to strip me of my citizenship, «Yabloko» decided not to nominate me after all. In the end, they nominated a different candidate for the district they had promised to support me in. This other candidate did not even know he would be taking part in the election.

It is a strange story. At that time I didn’t believe it was possible, that someone could be stripped of their own citizenship. Especially since I’ve had it my whole life. There have also been threats against my family, but back then they seemed even less real.

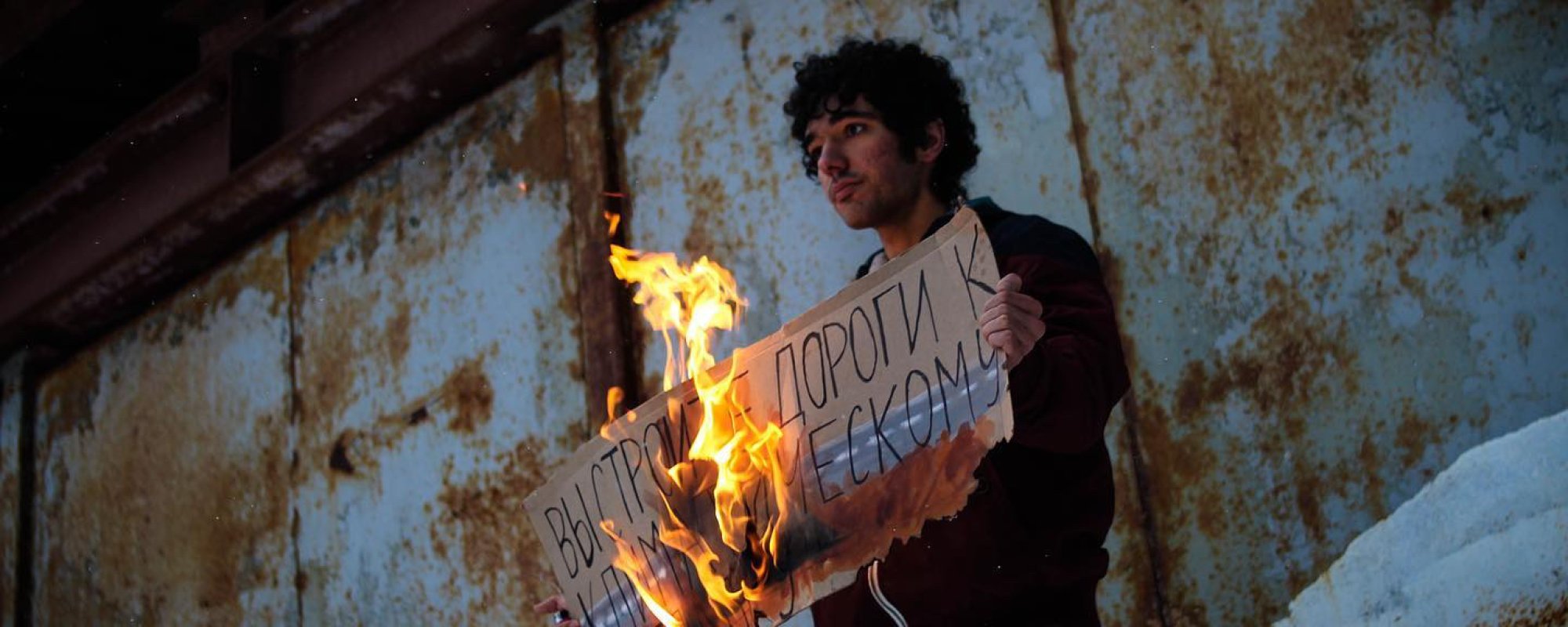

Arshak Makichyan in a picket, January 2020, Moscow / Photo from Makichyan's social networks

[In January 2022] My partner Polina (she doesn’t like being called a «wife») organized a protest and the cops waited by her house to get her. I helped her escape: Polina changed into my clothes so she could leave the house and after that, she hid at my place.

We decided to get married and went to Georgia at the end of January. Someone spied on us there as well. I’m not particularly observant, but Polina noticed the same person tailing us five to six times a day. The next day, the same individual took the flight to Moscow together with us.

Obviously, it wasn’t very safe for us [to stay in Russia], and that is why everyone was already asking us at the time if we were planning on staying in Georgia. But us being the Russian patriots that we are, we wanted to return and continue our activism no matter what.

Our wedding was scheduled for February 24. Since Putin started a war on the same day, I wrote «Fuck the war» on my shirt. Polina wore a blue dress and carried yellow flowers. We just planned to sign the documents and to celebrate modestly, we cancelled the big ceremony. But the photos from the wedding went viral, and were noticed by the western audience in particular. We were interviewed by Fox News, The Economist and other media. We told them that there are enough intelligent people in Russia who are currently speaking out and protesting against the war, we also told them about the protests, the thousands of detentions taking place.

On February 25, the day after our wedding, we were stopped near our house. Polina was initially planning to organize a protest, but was preemptively detained. Personally, I hadn’t been planning anything at all, I just wanted to go with her.

We canceled our trip to Armenia because we wanted to stay with our country, but in the end we understood that we would not be able to achieve anything. By mid-March, the protests were flooded with cops and there were fewer and fewer protesters taking part, so we decided to leave. I remember how every day, we waited [for the police] to search our apartment, because almost all our friends’ homes had been searched by then. It was clear that if we did not leave, one of us could be detained for a long time. Just recently, my friends were tortured while being questioned about the Case of the Mayakovsky Square poetry readings.

I didn’t want to spend several years in prison. It may be an interesting experience, but not necessarily a useful one. Even if Alexei Navalny is still able to hold people’s attention, many of the activists who aren’t as present in the media spotlight don’t have this chance.

We left on March 19. First, we bought bus tickets to Belarus, then to Poland and from there to Germany. Of course, we were scared that we would be detained on the road. The problems appeared on the border from Belarus to Poland. As it turned out, Poland was not letting in anyone whose Schengen visas had been issued by other countries and ours had been issued by Germany. We asked our activist friends from Poland to call the border post so that they could make an exception for us and in the end, they eventually let us through.

The airplane tickets via Turkey and Berlin would have cost us hundreds of thousands of rubles — money we did not have. I am against restrictions on Russians entering Poland, Finland and the Baltic countries. They need to show flexibility and look at each case separately. Perhaps tourism isn’t a great idea at the moment — but when activists travel using tourist visas it’s normal. We had tourist visas, it was difficult to get any other type.

In Germany I promote the fact that not all Russians are fascists and talk about what it’s like to live under a dictatorship. When we first arrived in Berlin we did several interviews a day.

Here I take part in demonstrations our climate movement organizes and I myself organize pickets and rallies. Hundreds of different protests are held here regularly and joining a picket is not anything unusual. It’s a completely different type of activism, and my Russian skills — for example, of not being afraid of the police — are not particularly valuable. However, I’m trying to find my own new activism.

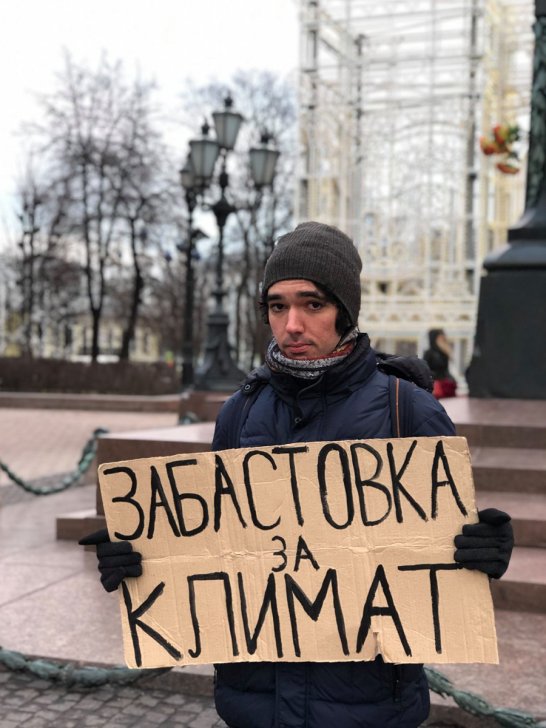

Polina Oleinikova and Arshak Makichyan / Photo: AREVIK

In May we were thinking about returning. I wrote on Facebook that we were planning to return in June. And just at the end of May, I received a notification via Gosuslugi that this thing had appeared [about deprivation of citizenship]. My family did not want publicity, so this whole time, I could not talk about it.

The court hearings went on for five months. As far as I understand, a formal reason was provided: the prosecution confirmed that my father applied for Russian citizenship at the beginning of the 2000s, but he was issued with the passport with violations of the formal processes. I do not remember the exact date of this, as I was a child.

The personal file, in which the grounds for obtaining a passport are recorded, has been lost, it simply no longer exists. This is a mistake by the officials, but they claim this as the grounds for withdrawing our citizenship. I don’t understand how it works, it’s a crazy formality. Among other arguments, they list the fact that the house in which we were registered is now in an uninhabitable condition. This is a strange reason for the deprivation of citizenship — many people in Russia live in houses that have not been repaired.

The is so contrived that you read the documents and do not understand what is written there, you have to ask the lawyers to explain it. As I understand it, we were deprived of our citizenship and registration, but we were not deprived of our property, as the prosecutor’s office had requested.

If you start taking away property from people who express their political views, speak out against the war — and not only from people, but also from their families! — it would turn out to be a pretty good tool of repression. So you can earn a lot of money by confiscating property and handing it out to those that are more loyal.

The decision was supposed to be announced last Monday, but it was not announced to us, which is also illegal. The judge went into the deliberation room and said she would call the next morning. When we called them the next day, we were told to wait for five days. They promised to send us the decision by mail but in the end, my father had to go pick it up himself. It was a very strange case. After a trial lasting five months the decision was not announced [in the presence of the parties to the process].

I provided a Power of Attorney for my lawyers and did not attend court myself. Initially, they filed a counterclaim, I didn’t really follow the trial. I just saw that time was running out. Either because the First Department has good lawyers, or because the system itself did not understand what to do. I was convinced that the trial would end with deprivation of citizenship. Because 99% of court decisions in Russia do not end in acquittal.

Polina Oleinikova and Arshak Makichyan at a protest in Berlin / Photo: Marie Jacquemin

I cannot claim asylum in Germany because then I would be stuck here and would not be able to work or to see Polina, who is currently studying in a different country. There are no obvious solutions.

I have just met with a lawyer, we discussed various options, but so far I haven’t made any decisions. It’s very difficult. A lot of people offer unsolicited advice without realizing how difficult the situation is. I am hoping for a reaction from European politicians who will offer me help, but there is no certainty.

I do not want to talk about what my family members will do in relation to the deprivation of citizenship. It’s their own business and they don’t speak out publicly.

Lots of people say that we should be happy, but somehow I’m not happy. It’s highly probable that my documents are invalid now. I don’t quite know how it works and I don’t think there are any real precedents — you have lived all your life, you have a marriage certificate issued in Russia, all your diplomas. I won’t be able to go anywhere or do anything in Europe if I don’t get granted citizenship.

I continue to use my social media accounts to speak up against the war. In recent months, I have been talking a lot about the problems of Russian civil society, and abroad too. People are scared of talking about it — it’s an uncomfortable topic.

We, the Russians, are seen as murdering Ukrainians, that we are to blame, that we did not do enough to stop Putin. Against this backdrop, it seems unethical to say that we are encountering problems with visas. It seems to me that this is logic leads nowhere. Europe has funded Putin all these years and turned Russia into what it is today.

Russian civil society really needs support so that it can continue to exist, at least online. There is an economic crisis in Russia, people are dissatisfied with the war. Now activism is even more important than it ever was before the war. Our voices should be heard in Europe: we know the situation in Russia better, we understand the Russians. I think it’s important to talk about that.

Media team OVD-Info